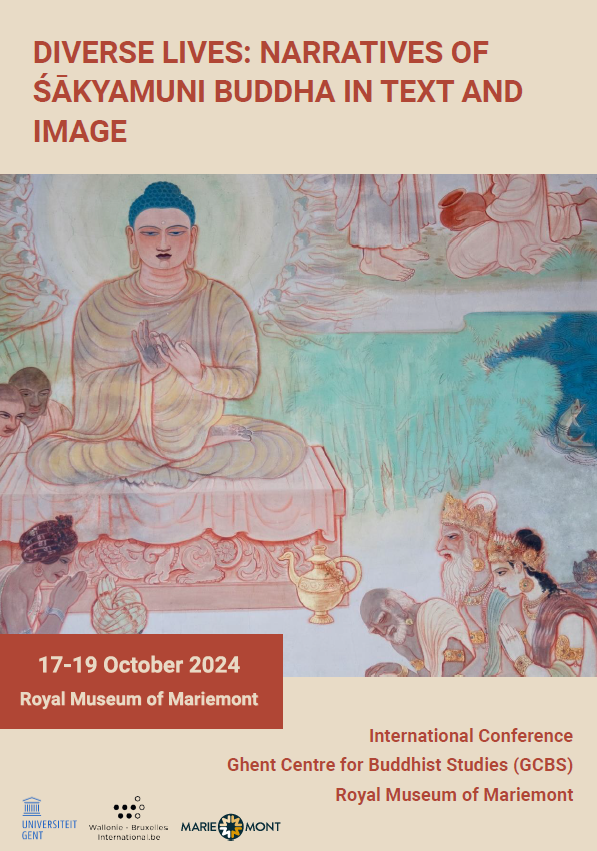

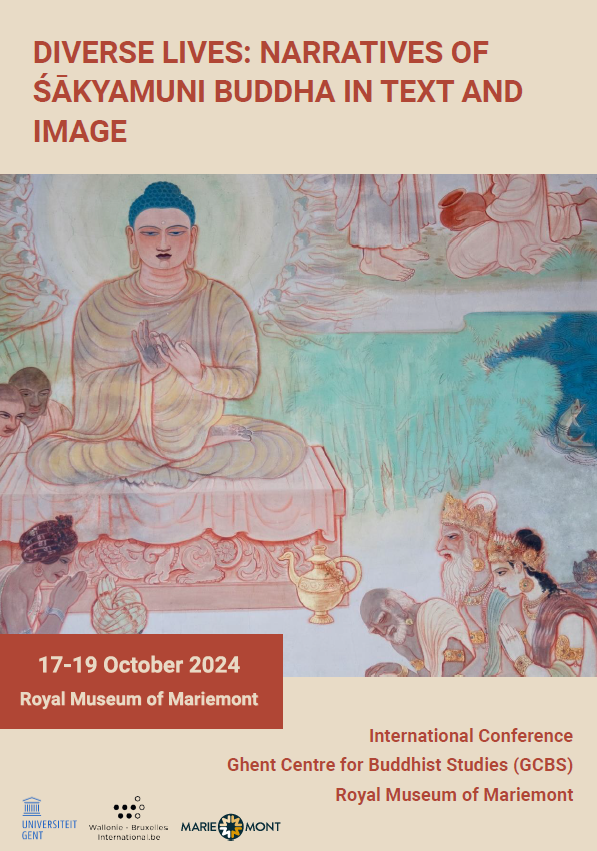

Śākyamuni Buddha, the founding figure of Buddhism, has played a profoundly significant role across South and East Asian – and more recently also Western – cultures and societies. Despite his central role, no single biographical account of his life is universally accepted by the diverse Buddhist traditions. Instead, the narratives of Śākyamuni’s life vary widely, reflecting the doctrinal and ritual diversity present across the different regions and schools of Asian Buddhism. In the absence of universally accepted textual and visual sources, even the key events of the Buddha’s life have been subject to numerous interpretations across both textual and visual media throughout Buddhism’s geographic spread and doctrinal evolution.

This conference aims to explore variations and interpretations of the Buddha’s life stories as found in diverse textual and visual materials. We will approach these narratives from an interdisciplinary perspective, encompassing fields such as religious studies, philology, literary studies, archaeology, and art history, among others.

Ghent Centre for Buddhist Studies (GCBS) and Royal Museum of Mariemont cordially invite you to attend the International Conference “Diverse Lives: Narratives of Śākyamuni Buddha in text and image” to be held on 17-19 October 2024 at Royal Museum of Mariemont (Belgium). For details, see below.

Please note that while entry to the conference is free, registration is mandatory and must be completed before the 12th of October. To register, please visit the following links:

Conference Registration:

https://forms.gle/v3LinnJ2CrmfQ6dJ8

Keynote Lecture Registration (In-person & Online; 18th October, 17.00-18.00, by Stephen F. TEISER):

https://forms.gle/tfuGrFvLpQyRjZo99

Timing: October 17–19, 2024

Location:

Royal Museum of Mariemont, Belgium

Chaussée de Mariemont 100,

7140 Morlanwelz (Belgium)

Organizers: Ghent Centre for Buddhist Studies (GCBS) & Royal Museum of Mariemont

Practical information

Getting to the Royal Museum of Mariemont

The Royal Museum of Mariemont is located in Belgium, approximately 50 km south of Brussels. The nearest airport is Brussels South Charleroi Airport, and the closest train stations are Morlanwelz and La Louvière-Sud.

Organization:

Prof. Dr. Ann Heirman, Universiteit Ghent

Dr. Lyce Jankowski, Royal Museum of Mariemont

Prof. Dr. Max Deeg, Cardiff University

Prof. Dr. Neil Schmid, Dunhuang Research Academy

We look forward to welcoming you to the event!

Conference program

(also available as a PDF file: Diverse Lives_Conference-Program_2024.10.16)

DAY 1 – Thursday 17th October

10.00 – Welcome address

SESSION 1: Life of the Buddha – Mural paintings

Chair: Neil Schmid (Dunhuang Academy)

10.30-11:00 – ZIN Monika (Leipzig University): “The Buddha and the Brahmins in Kucha Paintings”

11.00-11:30 – DOLLFUS Pascale (CNRS – Paris Nanterre University): “Comic Strips in Buddhist Temples? Narratives of Śākyamuni Buddha in Kinnauri Temples”

11.30-12:00 – YI Joy Lidu (Florida International University): “A Preliminary Comparative Study of Buddhist Narratives and Modes in Yungang Cave 6 and the Wangmugong Cave”

12.00-14.00 – Lunch Break

SESSION 2: Narratives re-examined (1)

Chair: Lyce Jankowski (Royal Museum of Mariemont)

14.00-14.30 – BOPEARACHCHI Osmund (CNRS-ENS & UC Berkeley): “The Birth of Bodhisattva Siddhārtha’s son Rāhula: From Divergent Textual Sources to Distinct Visual Narratives”

14.30-15.00 – HIYAMA Satomi (International College for Postgraduate Buddhist Studies): “Iconographical Turn of the Buddha’s Life Story in the Wall Paintings of the Rock-cut Monasteries of Kucha – With Focus on the Parinirvāṇa Story Cycle”

15.00-15.30 – PONS Jessie (Ruhr University Bochum): “Wandering on the Right Bank of the Swat River: Narratives of Śākyamuni Buddha in the Dir Museum, Chakdara”

15.30-16.00 – Coffee Break

SESSION 3: Narratives re-examined (2)

Chair: Anna Andreeva (Ghent University)

16.00-16.30 – SIRISAWAD Natchapol (Chulalongkorn University): “The Iconography of the Buddha Images Depicting the Miracles of Śrāvastī in Thai and Burmese Arts”

16.30-17.00 – VENDOVA Dessi (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston): “Taking the Bodhisattva into Town: The Forgotten Cult of the ‘First Meditation’ Image”

17.00-17.30 – TIAN Mengqiu (Heidelberg University): “’The Evolution of the Legend of Māra’s Daughters in Three Early Indian Literature”

DAY 2 – Friday 18th October

Parallel sessions

SESSION 4: Contemporary interpretations (1)

Room 1 (CRIE Park of Mariemont)

Chair: Charles DiSimone (Ghent University)

10.00-10.30 – AUERBACK Micah (University of Michigan): “The Buddha as a Sage of Global Stature in Japan, 1901-1984”

10.30-11.00 – HARRINGTON Laura (Boston University): “‘The Greatest Movie Never Made’: the Life of the Buddha as Cold War Politics”

11.00-11.30 – LIN Chia-Wei (University of Lausanne): “Translating Śākyamuni Buddha’s Life Story into Georgian – Balavariani in the Eurasian linguistic context”

11.30-12.00 – BARUA Kazal (International Buddhist College): “Depiction of the Buddha in Edwin Arnold’s The Light of Asia: Scriptural Authority and Literary Innovation”

SESSION 5: Biographical literature (1)

Room 2 (Boël Auditorium):

Chair: Max Deeg (Cardiff University)

10.00-10.30 – LETTERE Laura (University of Naples “L’Orientale”): “The Buddhacarita from India to Central Asia, to China: How the Poetic Narrative of the Life of the Buddha Shaped Chinese Imagination”

10.30-11.00 – HE Xi (Appalachian State University): “A Study of the Fo benxing jing (the Sūtra of the Buddha’s Original Life): A Buddha Biography Narrated by Vajrapāṇi”

11.00-11.30 – HUARD Athanaric (University of Munich): “Common Source or Imitation? Aśvaghoṣa’s Buddhacarita and the Fóběnxíng jīng 佛本行經”

11.30-12.00 – LEWIS Todd (Harvard University): “Sugata Saurabha, a mid-20th Century Narrative on the Buddha’s Life from Nepal”

12.00-14.30 – Lunch Break

14.30-17.00 – GUIDED TOUR of the EXHIBITION “Sensing the Buddha”

17.00-18.00 – KEYNOTE by Stephen F. TEISER (PRINCETON UNIVERSITY): “Praising Buddha’s Virtue: Constructions of Śākyamuni Buddha in Medieval Chinese Buddhist Liturgies” (Boël Auditorium)

DAY 3 – Saturday 19th October

SESSION 6: Text, Image and Art (Grand Auditorium du Musée)

Chair: Ann Heirman (Ghent University)

Boël Auditorium

10.00-10.30 – MAJER Zsuzsa (Dharma Gate Buddhist College): “Daily Buddha: Śākyamuni Buddha in the Daily-Chanting Ritual Texts of Tibetan Buddhism”

10.30-11.00 – APPLETON Naomi (University of Edinburgh): “A Family Matter: Vessantara/Viśvantara and the Life of the Buddha”

11.00-11.30 – JONES Christopher (University of Vienna): “Retelling Parinirvāṇa: Narrating Anew the Buddha’s (Apparent) Demise”

11.30-12.00 – Coffee Break

SESSION 7: Text, Image and Art

Chair: Neil Schmid (Dunhuang Academy)

12.00-12.30 – STORTINI Paride (Ghent University): “From Empire to Child’s Play: Nousu Kōsetsu’s ‘Images of the Life of Śākyamuni’ in Transnational and Trans-media context”

12.30-13.00 – VERMEERSCH Sem (Seoul National University): “The Buddha’s Biography as Tiantai Ideology”

13.00-13.30 – Closing Remarks

Keynote lecture

Friday October 18th

5.00 pm – 6.00 pm

TEISER Stephen F. ‒ Princeton University

Praising Buddha’s Virtue: Constructions of Śākyamuni Buddha in Medieval Chinese

Buddhist Liturgies

Medieval Chinese Buddhists produced no shortage of genres concerning the life of Śākyamuni Buddha. Early on, complete biographies as well as episodes in the vinaya were translated from Indic languages, and indigenous creations, including genealogies and encyclopedias, soon followed. In contrast to these better-known genres, this paper investigates the biographical fashioning of the Buddha in a neglected but important genre: liturgies. As texts composed to be recited aloud during the performance of life-cycle rituals, especially funerary rites and curing rites, liturgies offer an unrivalled record of how a wide range of people learned about Śākyamuni Buddha.

Since the Buddha was the first of the three jewels, most liturgies begin by praising him. These opening passages—often the most literarily sophisticated in the ritual text—draw attention to the specific powers and beatitudes of the Buddha that rituals aimed to harness. Buddhist liturgies thus disclose a praxis-oriented understanding of the Buddha’s life. My paper explores the particular virtues and life experiences of the Buddha that liturgists (and implicitly, their audience and sponsors) deemed important. Medieval liturgies typically use parallel prose (pianliwen 駢儷文, siliuwen 四六文), a literary style borrowed from the indigenous high ritual tradition. Accordingly, my paper draws on literary analysis and performance studies to analyze how ritual performers tried to accomplish their ends. My paper draws from two specific anthologies or handbooks of liturgical texts that circulated in manuscript form in Dunhuang in the ninth and tenth centuries, Za zhaiwen 雜齋文 and Zhuza zhaiwen 諸雜齋文. My paper suggests that, as aperformative genre—something other than literary text or visual image—liturgies provide another important way of narrating the life of the Buddha.

Abstracts

APPLETON Naomi ‒ University of Edinburgh

“A Family Matter: Vessantara/Viśvantara and the Life of the Buddha”

It has long been recognised that the Buddha’s past lives – including those narrated as jātaka stories – should be considered as a part of his lifestory. In this paper, I explore what we learn from viewing the most famous jātaka of all – the story of the extremely generous prince Vessantara – as a feature of the Buddha’s biography. In particular, I argue that the story adds three familial dimensions to the biographical endeavour: a sense of the value that the Buddha places on his family; a lesson in the importance, nonetheless, of overcoming family ties; and a demonstration that he is part of the lineage of the generous kings of Sivi. Overall, this story offers us a rich picture of how the Buddha relates to his family as he works his way towards Buddhahood and beyond. As such, the paper contributes to a growing scholarly interest in perceiving the Buddha’s lifestory as a communal effort, rather than an individual quest.

AUERBACK Micah ‒ University of Michigan

“The Buddha as a Sage of Global Stature in Japan, 1901-1984”

Since the Meiji period (1868-1912), representations of Buddha Śākyamuni in Japan have been strongly colored by comparison with his “global” counterparts. An essay for secondary school textbooks, published by the author and critic Takayama Chogyū in 1901, catalyzed this trend by ranking the Buddha as one of “Four Sages of the World,” along with Confucius, Socrates, and Christ. In 1904, the educator and philosopher Inoue Enryō established a “Hall of the Four Sages” in Tokyo, substituting Kant for Christ. However, Takayama’s selection returned in the “Four Sages” special issue of the intellectual journal Light of East Asia in 1912. When the career politician Adachi Kenzō founded the Hall of the Eight Sages in 1933, in what is now municipal Yokohama, he enshrined the Buddha as one of the four non-Japanese in the set—again, alongside Confucius, Socrates, and Christ. In 1984, when the artist Sugimoto Tetsurō at last completed his immense set of murals of the Ten World Religions, Confucius and Socrates were replaced by Laozi, Maṇi, and Mohammed, among others. This presentation will consider how twentieth-century representations of the life of the Buddha in Japan were modulated by the tendency to cast the Buddha as one sage among others.

BARUA Kazal ‒ International Buddhist College

“Depiction of the Buddha in Edwin Arnold’s The Light of Asia: Scriptural Authority and Literary Innovation”

Edwin Arnold’s The Light of Asia, a narrative poem on the life of the Buddha, gained immense popularity upon its publication in 1879. It became the most widely circulated book on Buddhism with over sixty editions in England and eighty in America and sales exceeding a million copies. Translated into thirty-five languages, it influenced art, literature, and culture for decades, captivating a global audience and inspiring many renowned figures.

However, critics argue that Arnold’s portrayal of the Buddha diverges significantly from native legends and traditional accounts, accusing him of misrepresenting both the Buddha’s life and teachings. Some suggest that Arnold’s depiction reflects more about the cultural context of 19th-century England and America than about the historical Buddha or Buddhism itself. Others contend that Arnold’s interpretation accurately captures key Buddhist ideas and serves as a valid source for understanding the Buddha’s life and philosophy.

Opinions also vary regarding the type of Buddhism presented in The Light of Asia. While some argue that Arnold predominantly reflects the older, southern form of Buddhism, others believe that his familiarity with Sanskrit should have led him to incorporate Mahayana elements in the poem, especially considering the emergence of significant Sanskrit texts in the late 19th century.

These differing perspectives underscore the need for further investigation to discern the precise nature of the Buddha portrayed in the poem. This paper, while re-examines the aforementioned claims, investigates the depiction of the Buddha in The Light of Asia comparing with its sources, the Victorian context, and traditional accounts of the Buddha’s life. It aims to address several key questions: What kind of a Buddha does Arnold portray in The Light of Asia, a portrayal that has been so widely received across the world? What serves the foundation of Arnold’s portrayal of the Buddha? And what insights does Arnold’s portrayal of the Buddha offer into the modern interpretation of the Buddha’s life and teachings in ways that are divergent or consistent with traditional Buddhist accounts?

BOPEARACHCHI Osmund ‒ CNRS-ENS & UC Berkely

“The Birth of Bodhisattva Siddhārtha’s son Rāhula: From Divergent Textual Sources to Distinct Visual Narratives”

Important events related to the life of Gautama Buddha are not homogeneously represented in ancient schools of art in South and Southeast Asia, and these differences are due to the confusion and irregularity of the way the events are narrated in sacred texts. Among the many episodes of this type, the events relating to the birth of Rāhula, Bodhisattva Siddhārtha’s son has given rise to major confusions in the sacred texts and, consequently, to divergent visual narratives. Taking this crucial event in the life of the future Buddha as the focus of this paper, I wish to examine how the Lalitavistara, the Mahāvastu and the Buddhacarita, as well as the Chinese and Tibetan translations of the original Sanskrit texts of the Abhiniṣkramaṇa sūtra and the Mūlasarvāstivāda vinaya, and Pāli literature, principally the Nidānakathā, have recounted this in diverse ways and how they lead to different visual narratives. The question arises whether Siddhārtha left the palace to become a recluse on the day his son Rāhula was born or not. The majority of Sanskrit texts firmly assert that Rāhula was not born when Siddhārtha left his home to become a recluse; on the contrary, Pāli texts assert that his son was born on the day of his renunciation. These opposing textual accounts have given rise to different iconographies dividing ancient and recent schools of Buddhist art into two camps, one inspired by Sanskrit texts such as Gandhāra and the other inspired by Pāli texts such as Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia.

DOLLFUS Pascale ‒ CNRS – Paris Nanterre University

“Comic strips in Buddhist temples? Narratives of Śākyamuni Buddha in Kinnauri temples”

Kinnaur, a passageway between India and Tibet, forms the eastern part of the Indian state of Himachal Pradesh. In this Himalayan region, Hinduism and Buddhism have been inextricably linked since at least the 10th century. Many people follow both religions, and it is common to find a Hindu temple and a Buddhist temple in the same compound, facing each other and built according to the same architectural rules. Since the Dalai Lama and the Tibetan government-in-exile settled in Dharamsala, thousands of Tibetan refugees have moved to Himachal, leading to a revitalisation of Tibetan Buddhism in the region. In Kinnaur, many stupas have been built and Buddhist temples renovated or fully rebuilt in the last few decades.

In this presentation, we will examine some recent paintings depicting the life of the Buddha that cover the walls of some of these newly renovated temples and question their sources of inspiration. While these paintings are reminiscent of the wall paintings of western Tibet in terms of their arrangement in registers and the presence of inscriptions providing information about the scenes painted, they differ from them in terms of aesthetics and style, but also, and this is our main point of focus, in the choice of episodes and in the way in which they are depicted. Thus, in the case of the birth and youth of the future Buddha, neither the prediction of the sage Aśita nor the various tournaments in which the young prince participated (such as the archery, wrestling and swimming contests) are described here. Conversely, there are episodes rarely found in Tibetan temples, such as the episode of the goose wounded by his cousin Devadatta, which is generally omitted in favour of the episode of the white elephant killed in a fit of jealousy. To conclude, we will reveal the quite unexpected source of these strange rarities.

HARRINGTON Laura ‒ Boston University

“‘The Greatest Movie Never Made’ – the Life of the Buddha as Cold War Politics”

“Greatest Movie” explores an unpublished 1953 screenplay on the life of the Buddha, conceived by a CIA-front organization called the Committee for a Free Asia (CFA) as a psychological warfare strategy to encourage American bloc-building efforts in Asia. “Tathagata: the Wayfarer” was written by a Hollywood screenwriter in collaboration with Ceylonese Buddhist scholar G. P. Malalasekera, who hoped the film would help him forge an “international Buddhism” in Asia.

I begin by unpacking the script’s diverse textual and visual sources, including Pali texts, Chinese Buddhist texts in translation, and American movies. Drawing on U.S. State Department and declassified CIA documents, I then read the screenplay through the lens of President Truman’s Campaign of Truth rhetoric and Malasekera’s Buddhist bloc-building agenda. “Greatest Movie” demonstrates a truth rarely recognized by scholars of Buddhism: for the early Cold War American state, the life of the Buddha was an object of foreign policy.

HE Xi ‒ Appalachian State University

“A Study of the Fo benxing jing (the Sūtra of the Buddha’s Original Life): A Buddha Biography Narrated by Vajrapāṇi”

This paper examines the important Buddha biography the Fo benxing jing (T193) (FBX), which has yet to receive full scholarly attention. FBX is generally considered one of two variant translations of Aśvaghoṣa’s Sanskrit court epic the Buddhacarita (Life of the Buddha, first century C.E.). By comparing the FBX with the Buddhacarita and its other known translation the Fo suoxing zan (T192), the Puyao jing (T186), the Lalitavistara, and other Buddha biographical materials in Chinese and Sanskrit, this paper contends that FBX differs significantly from the Buddhacarita and its Chinese translation Fo suoxing zan. Thus, it could not be a variant translation of the Buddhacarita. It was translated from a text that was created under the influence of the Buddhacarita, but it has its own significant emphasis and emotional tones. The text proclaims itself a Mahāyānasūtra, but some of its sectarian features indicate its affiliation with the (Mūla)Sarvāstivādin or Kāśyapīya traditions, which suggests the coexistence of the Mahāyāna groups with these traditions in the first few centuries CE. This paper employs both textual and visual materials to highlight four major themes in the FBX, i.e., the narrator Vajrapāṇi, the performance of the Great Miracle, the stories of Devadatta, and the display of the Buddha’s maitrībhāva. It hopes to offer insights into the textual history of FBX, its role in the Buddha biography tradition and in Buddhist art history, and its contribution to our understanding of Buddhism in the first few centuries CE.

HIYAMA Satomi ‒ Kyoto University

“Iconographical turn of the Buddha’s life story in the wall paintings of the rock-cut monasteries of Kucha – With focus on the parinirvāṇa story cycle”

In the Kucha Kingdom, which was once a major center of Buddhist culture in Central Asia, over a dozen of large structural and rock-cut monasteries were built under the initiative of the Sarvāstivādin school. As our book Traces of the Sarvāstivādins in the Buddhist Monasteries of Kucha (Vignato & Hiyama, 2022, New Delhi) demonstrated, these monasteries can mainly be classified into the two groups, the early Sarvāstivāda monasteries and late Sarvāstivāda monasteries. Interestingly, even though both groups operated under the Sarvāstivādins of the same region, a drastic change can be observed in the layout and iconographical program of their temple décor, including the representation of the Buddha’s life story in the wall paintings; while those in the early group mainly feature the episodes occurred during the Buddha’s lifetime, those in the late group emphasize the parinirvāṇa story cycle. The present paper aims at contextualizing this iconographical turn of the Buddha’s life story in the art of Kucha region into the historical situation of Buddhist cultural streams in Central and East Asia around the 6th century.

HUARD Athanaric ‒ University of Munich

“Common Source or Imitation? Aśvaghoṣa’s Buddhacarita and the Fóběnxíng jīng 佛本行經”

As is well known, Aśvaghoṣa’s Buddhacarita (AśvBC) has been translated into Chinese under the title Fósuǒxíng zàn 佛所行讚 (T192). However, the Chinese Buddhist canon also contains a similar text, the Fóběnxíng jīng 佛本行經 (T193), whose status is unclear. It has been proposed that this text is a Chinese composition, but this hypothesis can be refuted on several grounds: 1) the attribution to Bǎoyún 寶雲 found in the Taishō canon is incorrect, and this translation is older than T192; 2) the text shows a broad knowledge of Indian epic literature; 3) it was also translated into Kuchean (Tocharian B), as evidenced by fragments identified by the author.

This Indian text is closely related to the AśvBC. They share the same genre, literary style, general arrangement and, more importantly, certain parts of the verses. In certain chapters, such as the Mahāparinirvāṇa, the two texts exhibit parallelism throughout the narrative, with each verse typically sharing one or two pada. The existence of such similarities can only be explained by a genetic relationship: either one text imitates the other, or both draw from a common source. Given the prestige of Aśvaghoṣa, it seems reasonable to regard T193 as an imitation of his Buddhacarita. However, Aśvaghoṣa’s narrative contains a number of significant inconsistencies in episodes where T193 presents a coherent narrative in line with other biographies of the Buddha. Conversely, T193 contains clear innovations, such as the fight of the Bodhisattva against Māra, which is told as an epic archery duel. Consequently, the hypothesis of a common source, which was shortened and rearranged by both texts, is the only one that can be considered. This conclusion is of great importance for the reappraisal of the origins of Buddhist and Indian scholarly poetry.

JONES Christopher ‒ University of Vienna

“Retelling Parinirvāṇa: Narrating Anew the Buddha’s (Apparent) Demise”

An early and incredibly influential retelling of a Buddhist narrative is the Mahāparinirvāṇa-mahāsūtra: the Mahāyāna Buddhist account of the Buddha’s final teachings and death, perhaps composed in the third century CE. Unlike still older versions of the Mahāparinirvāṇa narrative, which are relatively consistent regarding the events surrounding the death of the Buddha, the Mahāyāna version presents all of this as a kind of display, produced by a teacher who is in fact already beyond the world and apart from bodily death, and changes a great many other details besides.

Long recognized as one of the most impactful Indian texts to have been transmitted to China (in two versions, in the early fifth century), in recent years the Mahāparinirvāṇa-mahāsūtra has come to the fore of scholarship concerned with buddha-nature teaching in India and elsewhere, for which it is an important early source. Without ignoring this and other doctrinal aspects of the text, this paper focuses on the literary and narrative dimensions of the Mahāparinirvāṇa-mahāsūtra, comparing our Chinese, Tibetan and Sanskrit sources for it with different witnesses to the older, “Mainstream” account of the Buddha’s death. The Mahāyāna narrative retains key characters and events from what came before, albeit with revealing changes. Given that at least some Indian audiences were likely aware of the traditional account of the Buddha’s final days, what were Mahāyāna authors doing by revising a pivotal episode in the history of their tradition? What were our authors prepared to keep, and what – in order to advance new ideas, or for some other purpose – did they change? We will also consider the matter of for whom the text may have been intended, which may suggest answers regarding what motivated such a radical reworking of a founding narrative about the Buddha and his legacy.

LETTERE Laura ‒ University of Naples “L’Orientale”

“The Buddhacarita from India to Central Asia, to China: How the Poetic Narrative of the Life of the Buddha Shaped Chinese Imagination”

The Buddhacarita defines itself as a mahākāvya, a large work of ornate poetry; it belongs to the genre of the sargabandha, i.e. a collection of chapters (sarga) linked together (bandha) into a story. It is a poem on the life of the Buddha composed in Sanskrit by the poet Aśvaghoṣa in the late first or early second century CE and it is the earliest example of ornate poetry (kāvya) – it tells the life of the Buddha from his birth to his first preaching. Only fifteen chapters of Aśvaghoṣa’s poem are available in Sanskrit, while the fifth century Chinese translation and the twelfth century Tibetan translation of the poem are in 28 chapters, perpetuating the Buddha’s first conversions and his parinirvāṇa.

The Chinese translation of the Buddhacarita, the Fo suoxing zan 佛所行讚, was completed by Baoyun 寶雲 (376?-449), a Chinese monk, in the first half of the fifth century CE; it is indexed as T192 in the Taishō edition of the Chinese Buddhist Canon. Overall, the Fo suoxing zan contains more information on the life of the Buddha than the original poem in Sanskrit – this seeming contradiction from the clash between our definition of “translation” and the conventional procedures of translation adopted by Buddhist translation teams in Medieval China.

The Fo suoxing zan qualified as the longest Chinese poem ever; although many licentious descriptions of courtesans were censored, possibly by the moral scrutiny of pious editors, the translation of the Buddhacarita introduced in China a very rich imagery, new metaphors, similes involving all the senses and it heightened narrative tension, particularly in the portrayal of Prince Sarvārthāsiddha’s familial relationships. This study will show how the stylistic and narrative features brought to Medieval China by the translation of the Buddhacarita significantly impacted Chinese imagination and literary productions for centuries. This influence extended beyond the Fo suoxing zan permeating various successful adaptations of the Buddha’s life, influencing the emerging courtly poetry in southern China and inspiring artistic endeavors in both China and Japan.

LEWIS Todd ‒ Harvard University

“Sugata Saurabha, a mid-20th Century Narrative on the Buddha’s Life from Nepal”

Every Buddhist community has a tradition recounting the life of Śākyamuni into its own vernacular narratives. The particular editorial and doctrinal choices as redacted from classical sources afford insight into the local history of Buddhist cultural adaptation; locally-composed and domesticated narratives were the “working texts” that shaped Buddhism in practice across Asia. This paper presents an example of this process in the case of Sugata Saurabha (“The Fragrance of the Buddha”), a modern book-length (356 pages) life of the Buddha from the Newar community of Kathmandu, Nepal. Adding to its exceptional qualities is the fact that the author composed this epic from 1940-45ce while incarcerated for cultural activism, having had his manuscript fragments smuggled out of prison.

Sugata Saurabha was written by one of Nepal’s greatest modern poets, Chittadhar Hridaya, and since its publication it has been a cultural landmark. My paper will discuss the text in its Newar context: as a product of his commitment to kāvya poetic tradition, contact with classical sources such as the Lalitavistara, Hindi translations of canonical texts published by Rahul Sankrityayana, publications of the Mahabodhi Society, and other sources.

This paper will draw upon Subarna Tulādhar’s and my translation published by Oxford in 2010, a work that was recognized by prizes from the Numata and Khyentse Foundations. In this talk, I will introduce the layers evident in this Buddha biography and incorporate research on the poet and this great work since then. Sugata Saurabha is a work blending Indic literary culture, Buddhist and Brahmanical, composed masterfully using end rhymes and over thirty metrical patterns from classical Sanskrit poetry. Sugata Saurabha reveals as does no other modern Newar work, to what extent the Indic cultural world has been alive for the traditional Newar elite. This presentation will show how Hridaya’s epic is paradigmatic of the local Buddha narratives and why it deserves a place among the great literary accomplishments of Buddhist history and modern world literature.

LIN Chia-Wei ‒ University of Lausanne

“Translating Śākyamuni Buddha’s Life Story into Georgian – Balavariani in the Eurasian linguistic context”

Barlaam and Josaphat (BJ) is the epitome of pre-modern transcultural, interreligious, cross-linguistic phenomena that took place on the Eurasian continent and beyond. BJ originated as a collection of Śākyamuni Buddha’s life stories translated from Indic into the now lost Manichaean Middle Persian version, which was in turn translated into Arabic (Kitāb Bilawhar wa-Būd̠āsaf), Georgian (Balavariani), Greek (Barlaam kai Iōasaph), and Latin (Barlaam et Josaphat, see fig. 1). BJ has enjoyed such great literary success and popularity that it was later translated into almost all medieval European vernaculars, and St. Barlaam and St. Josaphat were incorporated into Christian hagiography. When Jesuit missionaries arrived in China and Japan in the 16th century, they brought the stories of BJ along and translated these into early modern Chinese and Japanese, creating cultural “doublets” of the Buddha’s biography in Asia: medieval Buddhist versions from India and a Christian retelling in the early modern era (Fig. 2). The BJ is also a fascinating phenomenon from the linguistic point of view, as the translations span across at least four language families with distinct linguistic structures.

After an overview of the transmission of BJ from India via Europe to East Asia, the present paper will focus on the text of Georgian Balavariani from the perspective of transcultural studies, translation studies and historical linguistics, examining how Buddhist terms and proper names are transformed from the Indic original via Middle Persian into the Arabic Islamic version and from Arabic into the Georgian Christian version. Moreover, the study will identify parallels of the narrative elements in Balavariani from Chinese, Tibetan, Pali Buddhist canons and other Buddhist textual sources and observe how these are adapted, modified and remolded into a Christian hagiography. The paper will also consider narrative elements of Christian hagiography and Biblical citations added by the Georgian translator.

MAJER Zsuzsa ‒ Dharma Gate Buddhist College

“Daily Buddha: Śākyamuni Buddha in the Daily-Chanting Ritual Texts of Tibetan Buddhism”

As part of a recently started comparative study of the daily chanting ritual texts of Tibetan Buddhist monasteries of different Schools, the current presentation will focus on texts included in such daily chant books that are connected to Śākyamuni Buddha.

The texts of these collections are the most basic texts and prayers of Tibetan monastic education that novices memorize and learn first during the basic part of their training and then monks of the main assembly hall recite daily. Laypeople, devotees and practitioners similarly listen to the explanations of these texts first before meeting more deep, lengthy or philosophical texts or topics. The texts included in these can differ in each monastery as the different Tibetan schools (Gelug, Nyingma, Sakya, Kagyü, etc.) all have short prayers and texts characteristic of only them. Also, there are usually local texts included. Furthermore, in Mongolian textbooks or in Bhutan, etc. we also find texts characteristic of their Buddhist tradition only.

The number of texts differs from monastery to monastery, also influenced by the inclusion of the texts characteristic for the given School. Such a daily chanting may contain around 20-50 different texts. These texts are for recitation and most of them are written in verse. Several of them are canonical, being Kangyur (bka’ ‘gyur) or Tengyur (bstan ‘gyur) texts translated from Sanskrit. Many other texts were composed later or are ritual texts exclusively characteristic of Tibetan Buddhism. Also, different genres of Tibetan ritual literature are represented. There are considerable differences in the daily chanting of the individual temples but still there are texts that tend to appear in most of the prayerbooks, the most frequently recited basic texts.

The presentation will focus on Śākyamuni Buddha as he appears in the textbooks of Tibetan Buddhist daily ritual practice of different Schools and give an overview of the most often used texts connected to him. For example, we find praises or eulogies (bstod pa) of Śākyamuni and these might include mentions of his life story or deeds. Some other mentions of him will also be analysed in quotations from other texts of these prayer collections. Thus we will get an overview of Śākyamuni Buddha’s representation in Tibetan daily-chanting and his importance in these textual materials.

PONS Jessie ‒ Ruhr University Bochum

“Wandering on the right bank of the Swat river: Narratives of Śākyamuni Buddha in the Dir Museum, Chakdara”

As many have pointed out, the art of Gandhara marks an important stage in the development of a ‘reasoned’ hagiography of the Buddha. The arrangement of episodes in a chronological sequence that unfolds from right to left around the stūpa constitutes a mode of narration that deviates from the Buddhist arts of Sanchi, Bharhut, or the Andhra region. While Faccenna, Filigenzi, Behrendt, and Naiki have shown that various solutions existed and that the sequential juxtaposition of episodes was not the only principle governing the arrangement of episodes, many stories remain difficult to identify, and the data is often too fragmentary to enable a reconstruction of the narrative sequences and a nuanced understanding of Buddhist storytelling in Gandhara. For three years, the DiGA project (“Digitization of Gandharan Artefacts: A project for the preservation and study of Buddhist art from Gandhara”, BMBF eHeritage funding line) has documented a collection of approximately 1500 Buddhist sculptures preserved in the Dir Museum in Chakdara, Province of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa (KP), Pakistan. These sculptures come from a dozen archaeological sites in the Shah-kot/Talash zone (around modern-day Chakdara) excavated by the Directorate of Archaeology and Museum, KP, and the Department of Archaeology of Peshawar University in the 1960s and 1970s. Among these sites, those of Ramora, Andan-dheri, and Chatpat have yielded a wealth of sculptural material, including extensive portions of sequences of hagiographical episodes, allowing for a fine-grained study to better understand the larger Gandharan artistic phenomenon. Although the analysis of the corpus is only at a preliminary stage, a perusal of the material allows us to delineate certain tendencies in the rendering of the Buddha’s hagiography. Following proposed reconstructions for some of these narrative sequences, including an assessment of their original position in the Buddhist context, this paper will successively analyze the range of episodes illustrated, highlight the specificity of their visual treatment, assess their relation to literary traditions, and explore the logic(s) that govern the arrangement of scenes on the panel. Ultimately, this paper will reveal diverse and possibly localized modes of engaging with Buddhist stories and their literary formations. While there exists a certain homogeneity in structuring the life of Buddha chronologically across Gandhara, the archaeological record reveals a fluid process of storytelling that accommodates the evolving/local needs of various Buddhist communities.

SIRISAWAD Natchapol ‒ Chulalongkorn University

“The Iconography of the Buddha Images Depicting the Miracles of Śrāvastī in Thai and Burmese Arts”

The Great and Twin miracles displayed by the Buddha in Śrāvastī are among the Buddha’s principal miracles. They could even be an important episode of his career. The Buddha performs a series of miracles in Śrāvastī after having been challenged by the tīrthikas of the time in order to overcome their pride in the audience of rulers and other nobles as well as to convince and convert them to his doctrine. This famous and very important episode of the life of Buddha has been described beautifully in both mediums of text and art. The episode is preserved in multiple textual sources in a variety of languages transmitted by various schools. It has been represented in the visual art of ancient India, Central Asia, as well as Southeast Asia. In Thailand, the depiction is found in many artifacts in a complex composition from the ancient period of the Dvaravati, one of Thailand’s oldest religious and artistic cultures, and seems to carry its influence into the Ratanakosin period around the early 19th century CE. At Pagan, Burma, this narrative is depicted in mural paintings at many Buddhist sites. This research article focuses on the iconography of the Buddha images displaying the Śrāvastī miracles in the art of Thailand and Burma. The objective is to analyze the iconographic symbolism and artistic style of Buddha images found in Thai and Burmese sculptures, reliefs, and mural paintings that depict the Śrāvastī miracles. This study sketches not only the nature of Thai and Burmese art but also demonstrates how key elements of a narrative from literary sources have been transformed through visual representations. These artifacts depict both the selection of stylistic expression of Indian arts as well as adaptation of the local ingenuity.

STORTINI Paride ‒ Ghent University

“From Empire to Child’s Play: Nousu Kōsetsu’s ‘Images of the Life of Śākyamuni’ in Transnational and Trans-media context”

Recent scholarship has shown the importance of travel to South Asia and of the reimagination of ancient India in the construction of the idea of Buddhism in modern Japan (Richard Jaffe, Okuyama Naoji, Inaga Shigemi). The production of new visual culture inspired by early Indian art played an essential role and was often centered on narratives of the life of the historical Buddha Śākyamuni (Micah Auerback, Fukuyama Yasuko). While this scholarship has shed light on the importance of connecting visual culture with the intellectual construction of modern Buddhism, it has not taken into full consideration the material and media dimensions of this art. In this presentation, I will analyze scenes of the life of Śākyamuni produced in the 1930s by the Japanese painter Nousu Kōsetsu (1885‒1973), and later visual culture inspired by Nousu’s scenes and disseminated in a transnational context in various media. While the Indian aesthetics and the theme of the historical founder were used to universalize the modern image of Buddhism as a world religion, consideration of the materiality and medium in different historical and geographical contexts will shed light on the often discordant narratives that this visual culture produced. The original scenes made by Nousu for a temple in Varanasi projected modern pan-Asian ideology on the shared Buddhist heritage of India and Japan. The reproduction of the scenes in postwar children picture books, boardgames, and for a child-centered celebration of the birthday of the Buddha reveals a pedagogical use which stresses Buddhism as promoting intercultural communication. Finally, the same scenes inspired in the 1950s a series of woodcarvings at the Buddhist temple of Chicago that were aimed at suggesting how Buddhism could match American ideals of freedom, and in so doing easing the assimilation of the Japanese American community.

TIAN Mengqiu ‒ Heidelberg University

“‘The Evolution of the Legend of Māra’s Daughters in Three Early Indian Literature”

The legend of Māra’s daughters in the life of the Buddha is always associated with the scene of “Temptation”, which is an extension of Māra’s assault on the Buddha. For a long time, the study of the “Temptation of Māra’s daughters” has been considered subordinate to the theme of Māra, rather than being examined as an individual subject. Yet in fact, this scene can be seen as a standalone story both in the Buddhistic literature and in the visual-artistic tradition.

In today’s presentation, I will illustrate three early Indian literature (Sutta-nipāta, Māra-saṃyutta, and Lalitavistara) and examine the earliest development stage of the legend, how the legend was adapted and modified, and the possible reasons which contributed to the evolution.

VENDOVA Dessi ‒ Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

“Taking the Bodhisattva into Town: The Forgotten Cult of the ‘First Meditation’ Image”

With the notable exception of Gregory Schopen, the cult of the Bodhisattva Siddhartha image representing him as a prince during the life episode known as the First Meditation has not received much scholarly attention. At best seen as an interesting “floating episode” as it takes a different place in the narrative sequence depending on the version of the Buddha’s life, or at worst deemed as an “odd” and minor life event even by a scholar such as Schopen, this key life episode has eluded the attention it deserves. In this paper, apart from drawing upon different, including understudied, versions of the Buddha’s life, I will discuss extant early images depicting Siddhartha as a prince during his First Meditation from the early centuries C.E. (many of which are not identified or are misidentified), epigraphical records attesting to the image cult, and monastic code (Vinaya) texts of the Sarvastivadins and the Mūlasarvāstivādins recording the now-forgotten importance of the cult of the image of the Bodhisattva “under the jambu tree shadow.” These materials shed important light and demonstrate that the First Meditation image was once the center of an important monastic cult of the Bodhisattva Siddhartha and involved image processions and was feted during the most important Buddhist festival celebrating Śākyamuni’s Enlightenment, known as Mahāmaha, or Great Festival. I will also touch upon the connection between this image cult and the emergence of the popularity of the image of the “Pensive Crown Prince” (Ch. siwei taizi思維太子), also known as “Pensive Bodhisattva.” An image that likely first originated in India and Gandhara and consequently became very popular in East Asia, where its indicative meaning changed with time but still stood as a further witness to the important but now forgotten image cult.

VERMEERSCH Sem ‒ Seoul National University

“The Buddha’s Biography as Tiantai Ideology”

The earliest biography of the Buddha that has come down to us from the Korean peninsula is the Sŏkka yŏrae haengjŏk song (Odes on the Acts of the Tathāgata Śākyamuni, 1328). It consists of 840 verses, which are interspersed with lengthy commentaries. Although it is in many ways a conventional biography that leans heavily on earlier Chinese biographies, it is unique for trying to infuse the life story of the Buddha with Tiantai teachings. Thus, after the Buddha’s enlightenment his preaching career is divided into five stages, culminating in the final revelation of the teachings of the Lotus Sutra. The preaching of the Lotus sutra is skilfully integrated into the life story, with heavy emphasis on Tiantai ideas such as the provisional and the real, the uniting of the three vehicles into one, and the different levels of attainment. This paper will first and foremost try to explain how the text’s author, the monk Mugi (fl. 1328), infuses Tiantai ideology into conventional sources of the Buddha’s life. It will also address the question of Tiantai’s position towards other schools, notably Pure Land and Chan Buddhism. Despite the emphasis on the all-encompassing enlightenment offered by the Lotus sūtra’s teachings, the text is also replete with end-of-dharma soteriology, creating an interesting tension. The text furthermore integrates the Chan legend of the transmission to Kaśyapa (smiling upon holding up a flower), which reveals a peculiarity of Korean Tiantai (i.e. Ch’ŏnt’ae), namely its attempt at integration the Chan (K. Sŏn) school. Finally, the presentation will also try to shed light on the text’s influence on later Korean biographies of the Buddha.

YI Joy Lidu ‒ Florida International University

“A Preliminary Comparative Study of Buddhist Narratives and Modes in Yungang Cave 6 and the Wangmugong Cave”

Narrative is a universal phenomenon. It is international, transhistorical and transcultural. It is present in every age, every place, every society, and begins with the very history of mankind. Buddhist narratives are both history and legend, truth and fiction. Some are more historically based, whereas others are full of miracles. This paper attempts to investigate the visual representations of Buddhist narratives and their possible associations with Buddhist texts, as well as the modes of Buddhist narratives, using Yungang cave 6 and the Wangmugong cave 王母宮窟in Gansu as two case studies. Cave 6 is a central-pillar cave. The images are exquisite and unparalleled and cannot be compared with any others. There are more than thirty Buddhist stories, from his birth to his archery training, to the great departure tale, etc. However, among the rich biographical themes, the life of the Buddha ended abruptly with his first sermon at the deer park, and the Buddha’s Nirvana episode is not portrayed. Why is this important moment of his life and a very popular theme in other regions and cultures not depicted in the cave? Is this related to Buddhist scriptures such as the Lalitavistara and the Sūtras on Causes and Effects of the Past and Present? In addition, how and why are these narratives represented in various modes. Moreover, some are seen at the same level as the visual horizon of the human eye. Does this have anything to do with the functions of the caves? More importantly, why do the Wangmugong cave in north-western China and Yungang cave 6 in Shanxi share many striking similarities: the architectural layouts, the iconographic narratives and styles? The former only became known to scholars after the expeditions of Landon Warner (1881-1955) of the Fogg Art Museum of Harvard University and Horace Jayne (1898-1975) of the University of Pennsylvania of Archaeology and Anthropology to northwest China in 1924 and 1925. However, hitherto, scholars have not paid much attention to the cave and the intrinsic connection between the two. The enquiries to these issues would help us reconsider the function, ritual practices and execution of the caves. It would also be useful to understand the cultural exchanges and interactions between the regions. An investigation to the visual narratives of cave 17 in Ajanta, in comparison with Yungang cave 6 would also broaden our horizon in this respect.

ZIN Monika ‒ Leipzig University

“The Buddha and the Brahmins in Kucha Paintings”

The enormous number of narrative depictions in the wall and vault paintings of Kucha provides a unique opportunity to analyse them regarding the frequency of their occurrence. Multi-scenic cycles of the life of the Buddha – except the cycle of episodes concerning the parinirvāṇa – are scarcely found. More often we encounter episodes united into one scene with the Buddha at the centre, for example Māravijaya and Indra’s visit to the Buddha meditating in a cave. These episodes, however, are linked to specific locations in the cave architecture, which explains their repetition.

Far more frequent are episodes showing various encounters of the Buddha with different beings – not only humans but also animals and various good and evil deities. Such episodes are usually shown as so-called sermon scenes, a very special type of narrative representation that was developed in Kucha; it employs clearly defined, highly conventional rules to depict several sequences of action in one concise image.

The format of the “sermon scene” allowed for the illustration of a huge number of narratives. Illustrations of 100 stories in one temple are not unusual. Not all these images have been explained to date, but even if we cannot elucidate their content, their protagonists are easily recognisable. It is surprising how often the stories of – both good and evil – Brahmins are repeated in them, although the presence of a Hindu population or knowledge of the iconography of their members cannot be taken for granted in remote region of Kucha.

Conference photos:

Practical information

Practical information One buddha, many buddhas

One buddha, many buddhas

A closer look

A closer look